rheumatoid arthritis

- related: Rheumatology

- tags: #rheumatology

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

- genetic risks:

- 60% of risks

- HLA class II most important, especially HLA-D

- These HLA code for citrullinated peptide antigen that are immunogenic since citruline is not normally in humans

- citrulline formed by peptidylarginine deiminase

- environmental: 40%

- smoking activates PADI and citrullination, increases risk to 2-20x

- infection

- periodontal:Porphyromonas gingivalis

- Others: mycoplasma, Epstein-Barr virus, and parvovirus B19.

- hormones

- women more likely to develop RA

- estrogen appears to be proinflammatory and proautoimmune

Diagnosis

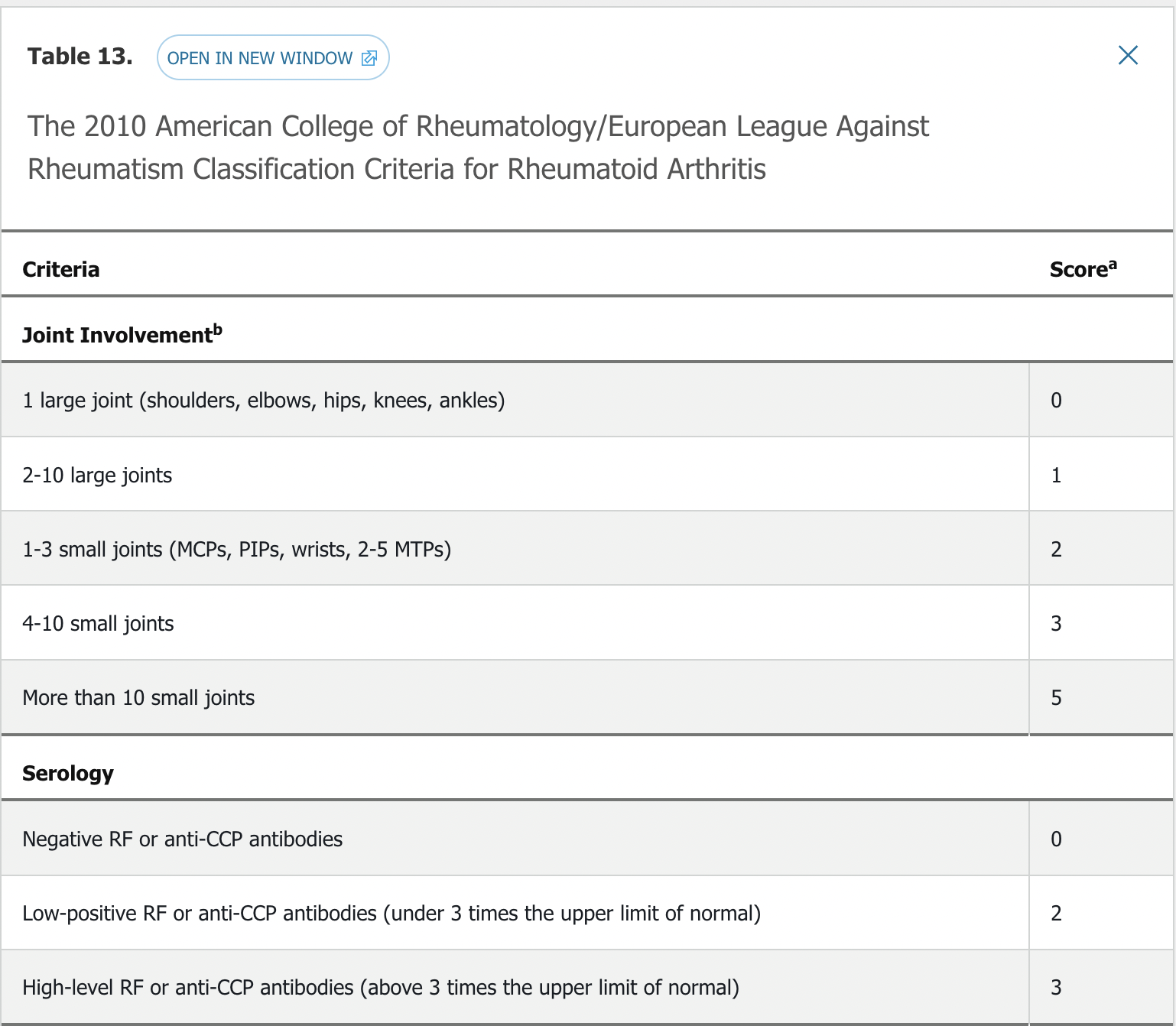

- 6 points need to classify as RA

Symptoms

- gradual onset

- symmetrical joint pain

- from joint damage

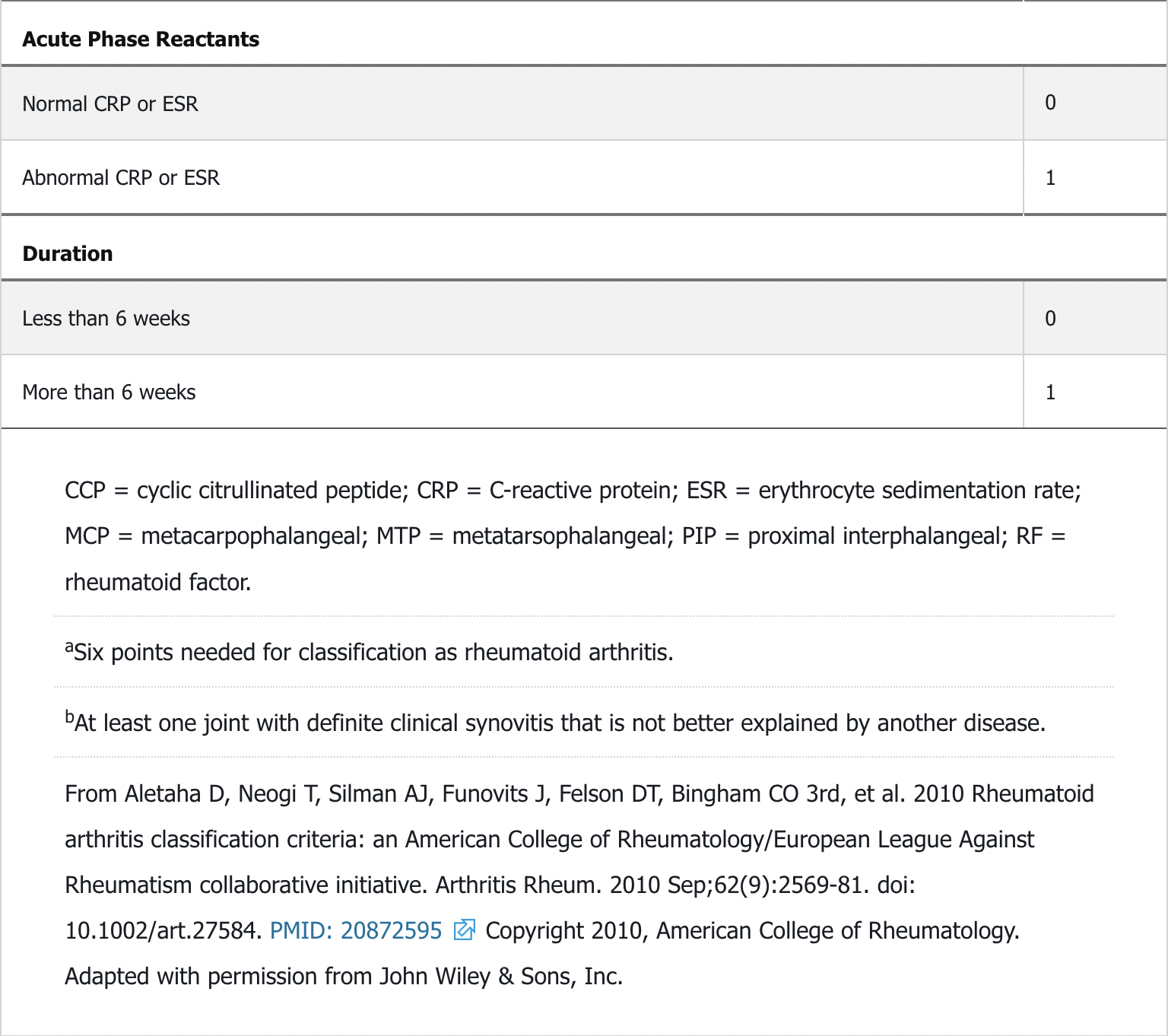

- synovitis: thickened lining, production of cartilage damaging metalloproteases. RANKL made by inflammatory cells activates osteoclasts to erode bones

- but may present as persistent involvement of a single joint

- metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP)

- metatarsophalangeal joints (MTP)

- proximal interphalangeal joints (PIP) of the hands and feet

- wrists, elbows, shoulders, hip, knees, ankles

- spares the distal interphalangeal joints (DIP) of both the upper and lower extremities

- spares T and L spine but affects C spine, especially C1-2

- inflammatory sx:

- joint swelling, palpable on exam, bogginess

- morning stiffness lasting hours

- stiffness better with activity

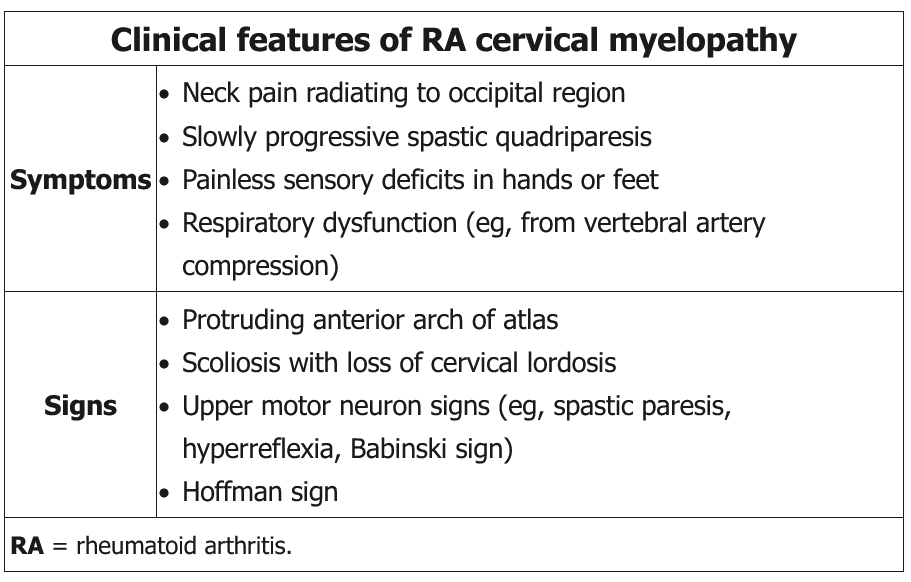

Patients with long-standing (generally 10 years or more) rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are at risk of developing C1-C2 subluxation. Inflammation from RA can lead to attenuation of the transverse ligament that normally limits the posterior motion of the odontoid process of the C2 vertebrae. Instability around the odontoid can impinge upon posterior structures, including the spinal cord and vertebral arteries. Common symptoms include a sensation of the head falling off, drop attacks, and painless paresthesia of the hands and feet; rarely, sudden death can occur. Initial imaging should be radiography of the cervical spine with flexion/extension views; if results are abnormal, MRI should then be performed. Consideration of surgery is necessary for patients with significant subluxation, especially if symptomatic. Patients with long-standing RA undergoing general anesthesia for any kind of surgery should have cervical spine radiography with flexion/extension views to assess for atlantoaxial subluxation, which can lead to neurologic compromise when the neck is extended during intubation.

extra-articular

- skin:

- rheumatoid nodules: up to 30% pts, usually in olecranon areas but also in hands/feet/lungs

- neutrophilic dermatoses: Sweet syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum

- palpable purpura from vasculitis

- eye

- dry eye (keratoconjunctivitis sicca)

- dry mouth (secondary sjogren)

- <1% episcleritis and scleritis

- keratitis: corneal inflammation

- scleritis and keratitis require immediate ophthalmology referral

- lung

- air trapping disease in up to 50% people

- pleural disease in up to 5%

- bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis

- large exudative pleural effusion

- low glucose

- low pH

- mimicks bacterial, TB, malignancy

- low complement levels

- elevated protein, RF, LDH

- mononuclear inflammatory cells: lymphocytes, monocytes

- heart

- mostly atherosclerosis

Felty syndrome

Anemia of inflammation is the most common RA hematologic abnormality. Felty syndrome consists of neutropenia and splenomegaly and occurs in patients with long-standing, severe, seropositive RA. These patients are at risk for serious bacterial infection, lower extremity ulceration, lymphoma, and vasculitis. With current treatment, Felty syndrome has become rare. Patients with RA can also have a large granular lymphocyte syndrome that can progress to large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Findings overlap with Felty syndrome and include neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly, and recurrent infections. Patients with RA are at increased risk for lymphomas (particularly large B-cell lymphomas), and risk is correlated with disease activity.

Scleritis

RA is one of the most common diseases associated with scleritis. Typical features include eye pain, pain with gentle palpation of the globe, and photophobia, (pain with eye movement). The deep scleral vessels are involved and may lead to scleromalacia, which is characterized by thinning of the sclera and is seen as a dark area in the white sclera. Scleromalacia may lead to perforation of the sclera called scleromalacia perforans. Scleritis can be vision-threatening and lead to blindness; it is therefore important to urgently refer the patient to an ophthalmologist for care.

Blood Vessels

A small-vessel cutaneous vasculitis occurs in a small percentage of patients with RA, leading to palpable purpura or periungual infarcts. A very rare, larger-vessel vasculitis similar to polyarteritis nodosa can affect multiple organ systems; prior to current therapy, it had a 5-year mortality of 30% to 50%.

Labs

- anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP):

- most useful, in 70% pts but specificity of 95%

- predictive for erosive disease

- Rheumatoid factor (RF): found in 70% of pts but also in other autoimmune diseases

- ESR/CRP: usually elevated and used to monitor treatment response

- seronegative patients

- 10-20% of diagnosed pt

- negative RF or anti-CCP

- better prognosis

- others

- anemia of inflammation

- modest thrombocytosis

Rheumatoid factor is an IgM antibody directed against the Fc portion of IgG immunoglobulin. Although characteristically associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), rheumatoid factor is present in fewer than 70% of patients with RA and is common in several other diseases. Anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies are more specific for RA but less sensitive. The presence of both autoantibodies together increases the likelihood of RA.

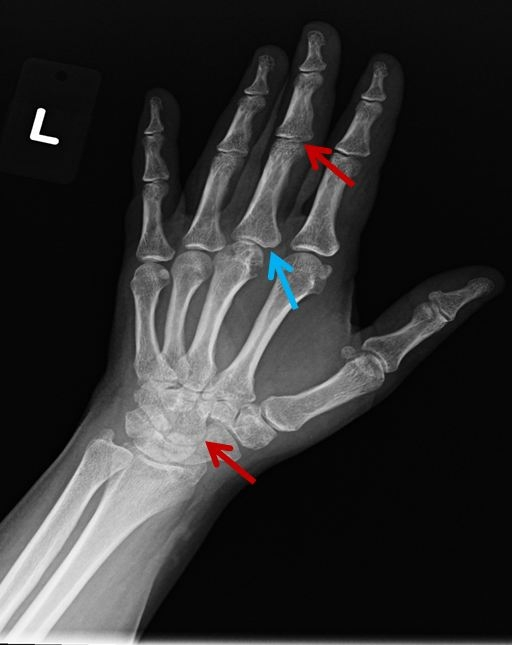

Images

- early xray can be normal

- plain xray hands/feet

- standard imaging study for diagnosis and progression

- periarticular osteopenia

- marginal erosions

- joint space narrowing

- xray C spine with flexion/extension for C1-2 subluxation

- MRI/US: more sensitive than xray and are sometimes used to determine response to therapy and progression

- US: standard for joint fluid, synovial tissue thickening, early erosions, increased vascularity

- MRI: bone marrow edema, synovitis, erosions

Advanced RA: ulnar deviation, marginal erosions (arrows), joint space narrowing, loss of ulnar styloid (arrowhead)

Advanced RA: ulnar deviation, marginal erosions (arrows), joint space narrowing, loss of ulnar styloid (arrowhead)

Marginal erosions and joint-space narrowing (arrows). Erosion at the fifth metatarsophalangeal joint is often the first radiographic sign of rheumatoid arthritis foot involvement.

Marginal erosions and joint-space narrowing (arrows). Erosion at the fifth metatarsophalangeal joint is often the first radiographic sign of rheumatoid arthritis foot involvement.

Radiographic erosions ("marginal erosion"), such as the left 3rd metacarpophalangeal joint in this patient (blue arrow), can suggest RA and indicate underlying erosive RA. These erosions eventually lead to joint inflammation and loss of joint space (red arrows).

Radiographic erosions ("marginal erosion"), such as the left 3rd metacarpophalangeal joint in this patient (blue arrow), can suggest RA and indicate underlying erosive RA. These erosions eventually lead to joint inflammation and loss of joint space (red arrows).

Management

General Considerations

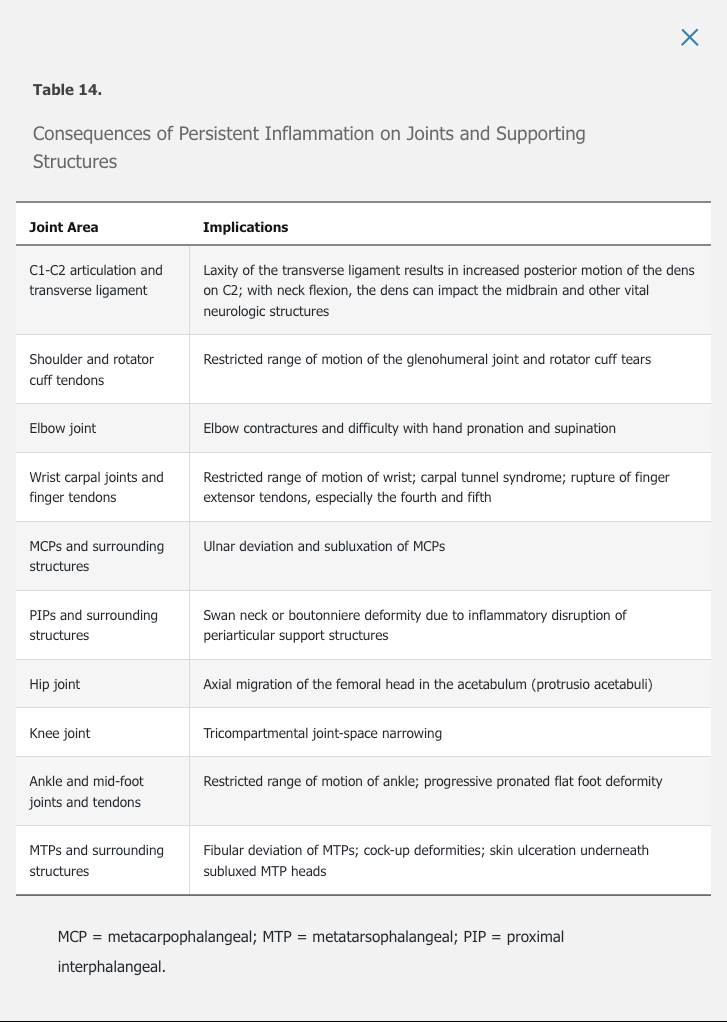

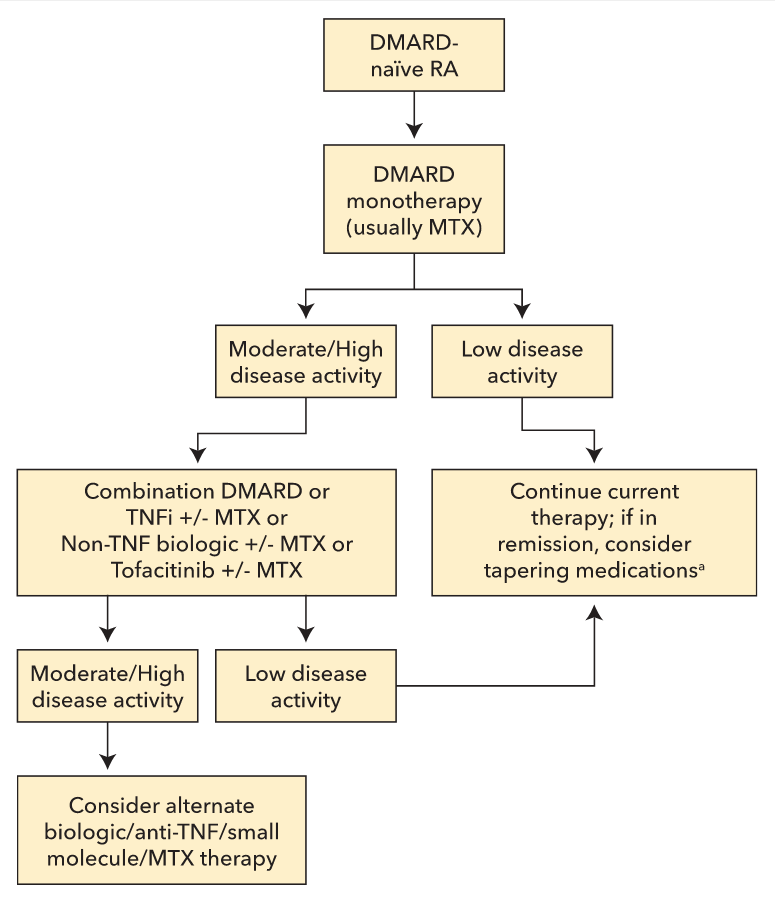

The 2015 ACR RA treatment guidelines advocate for early diagnosis and aggressive early therapy of RA to prevent irreversible cartilage and bone damage. The 2010 ACR RA classification criteria emphasize sensitivity to permit early diagnosis and institution of disease-modifying therapy (see Table 13). A key treatment goal is to treat to target, with the target being achievement of remission or low disease activity. Disease activity assessment involves making a measured determination using combinations of numbers of tender and swollen joints (typically utilizing 28 joints that exclude the feet), patient and physician impressions of disease activity, and, in some activity scoring systems, measurement of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein. These parameters are combined into a composite score, thus assigning a disease activity ranging from remission, to low, moderate, or high. The Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) are two commonly used instruments to assess disease activity and response to treatment. Treating to target in RA results in less radiographic damage, reduced cardiovascular risk, and increased work productivity compared with conventional care.

The 2015 ACR RA treatment guidelines can assist in making initial treatment decisions in early RA. Treatment is typically advanced at 12-week intervals with the goal of reaching remission or low disease activity as rapidly as possible. Patients who remain in remission or a low disease activity state for 6 months or longer may be able to reduce treatment intensity. Treatment decisions for established RA are more complex. An initial approach to the treatment of both early and established RA is outlined in Figure 6.

A simplified algorithm presenting an initial approach to the treatment of both early and established rheumatoid arthritis (RA). All patients with RA should receive a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug initially and be advanced to more aggressive and/or combination therapy as needed to control disease. Disease activity should be assessed, wherever possible, using a formal, validated, and consistent disease activity index. Refer to the American College of Rheumatology RA treatment guidelines for more complex algorithms accounting for differences between agents and patient-specific complexities. DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX = methotrexate; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

A simplified algorithm presenting an initial approach to the treatment of both early and established rheumatoid arthritis (RA). All patients with RA should receive a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug initially and be advanced to more aggressive and/or combination therapy as needed to control disease. Disease activity should be assessed, wherever possible, using a formal, validated, and consistent disease activity index. Refer to the American College of Rheumatology RA treatment guidelines for more complex algorithms accounting for differences between agents and patient-specific complexities. DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX = methotrexate; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Nonbiologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Methotrexate is the anchor drug in RA, used in both monotherapy and combination therapy. It can be titrated to doses as high as 25 mg per week in partial responders; the treating physician should generally maximize methotrexate dosing before adding other agents. At doses greater than 15 mg weekly, methotrexate oral absorption approaches its effective limit; switching to subcutaneous administration allows for higher serum drug levels. Folic acid supplements minimize toxicity without diminishing efficacy. Of patients with RA taking methotrexate alone, 30% to 50% achieve remission or low disease activity.

Sulfasalazine, leflunomide, and hydroxychloroquine also can be used as monotherapy agents in RA. Leflunomide may be useful in those who cannot tolerate methotrexate. Hydroxychloroquine is the least potent agent but can be used in very early disease when the disease activity score is low. It is also used as part of triple therapy (methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine). Data suggest that triple therapy is comparable to methotrexate combined with a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor, except in the area of radiographic progression.

Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Biologic DMARDs can be used as monotherapy but are typically added to methotrexate when moderate to high disease activity persists. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors are the most frequently used biologic DMARDs; these agents have a relatively rapid onset of action and demonstrate synergy with methotrexate. The combination of methotrexate and a TNF-α inhibitor has also been shown to have a “disconnect effect,” meaning that even patients with continued clinical disease activity may demonstrate little to no damage to cartilage and bone. This effect also has been shown with rituximab or tocilizumab in combination with methotrexate. Other biologic DMARDs used in RA include abatacept (a selective T-cell costimulation modulator) and tofacitinib (a small-molecule Janus kinase inhibitor).

Until better data are available to guide therapeutic decisions, choice of a biologic DMARD remains empiric and based on patient characteristics, including what agents should be avoided due to patient comorbidity (for example, avoiding abatacept in a patient with COPD).

NSAIDs

NSAIDs were once the mainstay of therapy of RA. These agents are not disease modifying and do not prevent joint damage. They are used primarily to control symptoms while waiting for the full effect of DMARDs to be realized or in patients with postinflammatory osteoarthritis.

Glucocorticoids

Unlike NSAIDs, glucocorticoids may have a disease-modifying effect. A recent study tested 10 mg/d of prednisone versus placebo for 2 years in combination with methotrexate; the prednisone group had no more side effects than the placebo group but gained better control of disease activity, used less methotrexate, needed fewer additional medications, and had less radiographic damage. Low-dose prednisone (5-10 mg/d) can be used to rapidly improve RA symptoms while waiting for long-term medications to become effective, or they can be used short term for disease flares. Long-term therapy with glucocorticoids, however, may be associated with substantial adverse effects including osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, and infection.

Surgery

Surgical therapy has become much less common in RA with current treatment strategies. However, some patients may require a synovectomy for a single persistently swollen joint, carpal tunnel release, repair of a ruptured tendon, total joint replacement (shoulder, metacarpophalangeal joints, hip, knee, or ankle), or joint fusion for a painful damaged joint (wrist or ankle). See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for a discussion of perioperative RA medication management.

Pregnancy

There is an increased risk for developing RA in the first year after a first pregnancy. Breastfeeding may decrease this risk. For women with established RA, two thirds will go into remission or low disease activity during pregnancy, and one third will not improve or will get worse. Medication management is a major issue, and pregnancy plans should be discussed with any woman of childbearing age who will be placed on therapy. A discussion of RA medications in pregnancy is located in Principles of Therapeutics.